On the matter of how realistic it is to achieve the set goals of the National Development Strategy until 2030, its particulars and mechanisms of implementation, specially for cabar.asia, shared their opinions experts from Tajikistan, Parviz Mullojanov and Khursand Khurramov.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“The return of labor migrants has reached critical mass in the course of the economic crisis facing their country of destination. This influx of returning labor migrants is also capable of exerting influence on the demographic structure of the population, labor market and socio-political stability. It is could also lead to a further deterioration in certain deteriorating criminogenic factors in the country, which is also incredibly undesirable for society”, – economist Anvar Babaev analyzes a series of problems facing labor migrants after they return to their homeland in this cabar.asia exclusive.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“The signing of the “Bologna Process” opens ample opportunities for Tajik students, but the implementation of the system in this country is not being accorded with international standards, which leads to negative consequences”, – specially for cabar.asia, Komron Hidoyatzoda, a political analyst, deliberates over the issues of the education system in Tajikistan.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“In just 10 years, China went from a country that did not substantially participate in the financing of the Tajik economy to becoming a major donor. Obviously, there is a simple and comprehensive answer to the question ‘why did it happen?’”- economist Konstantin Bondarenko, writing specially for cabar.asia, states regarding the hidden risks in the nature of Tajikistan’s external debt.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“Dushanbe is extremely interested in the development and deepening of trade and economic relations with Turkey and tries to avoid politicizing the relationship. At the same time, the political regime in Dushanbe is aimed at the complete secularization of society, with a certain apprehension seen in the growth of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party “, – political scientist Khursand Hurramov, writing specially for cabar.asia, evaluates the development of Tajik-Turkish relations.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

During the entire post-Soviet period, Turkish diplomatic efforts have focused on establishing close political, trade, and economic relations with Central Asian countries. Intimate ties with the region’s newly independent states gave Ankara some chances to limit Russia’s ability to consolidate its position and prevent the expansion of Iran’s influence, thereby underlining its importance to the West.[1] Former Turkish Foreign Minister Ismail Cem stated in one article that, “Turkey, in the aftermath of the Cold War, assumed a far greater geo-political and strategic role at the center of a vast landmass stretching all the way from Europe to the center of Asia.”[2] Moral and political support for Ankara’s aspirations originated in 1991 as the United States, Britain, and NATO leaders worried about the prospect of Iranian political and ideological expansion in the region.[3]

During the entire post-Soviet period, Turkish diplomatic efforts have focused on establishing close political, trade, and economic relations with Central Asian countries. Intimate ties with the region’s newly independent states gave Ankara some chances to limit Russia’s ability to consolidate its position and prevent the expansion of Iran’s influence, thereby underlining its importance to the West.[1] Former Turkish Foreign Minister Ismail Cem stated in one article that, “Turkey, in the aftermath of the Cold War, assumed a far greater geo-political and strategic role at the center of a vast landmass stretching all the way from Europe to the center of Asia.”[2] Moral and political support for Ankara’s aspirations originated in 1991 as the United States, Britain, and NATO leaders worried about the prospect of Iranian political and ideological expansion in the region.[3]

Mutual Interests

However, it is worth noting that in the political sphere, with Tajikistan not being a part of the Turkic world, it is left out of the overall design. Despite the shared religious identity between the two countries, bilateral relations have remained at the level of economic partnership. This is primarily due to the fact that no religious and historical-geopolitical motivation lies at the heart of Turkey’s foreign policy vector.

In geopolitical terms for Tajikistan, Turkey has traditionally been inferior not only to Russia and China but even to Iran with which Tajikistan has a common cultural and civilizational framework.

Soberly assessing their capabilities, Turkish foreign policy towards Tajikistan was originally aimed at obtaining economic dividends. Dushanbe, in turn, which started the ’90s dealing initially with the permanent political and then economic/financial crisis, was interested in finding not only potential donors, but also new ideological foundations. In such circumstances, the Turkish model of development, which implies the formation of a secular state, seemed the most attractive to the Muslim country.

Trade and Economic Cooperation

Turkey presents a successful example of political and economic transformation as well as a robust foreign policy. This trend can be seen in respect to Tajikistan.

As of the beginning of 2014 according to Turkey’s Ministry of Economy, Turkey’s share in Tajikistan’s construction sector amounts to $500 million with a total of 37 implemented projects. Turkish direct foreign investment in Tajikistan, according to the same agency, totals $130 million. The Kaynak shopping center in Dushanbe was built in part with Turkish capital around US $10-11 million. Turkish companies were also the contractors for large construction projects, including the Hyatt Regency hotel complex and the strategic Dushanbe-Kulob-Kulma-Karokurum highway linking Tajikistan and China.[4] In addition, in 2006, the Turkish company Bursel Holding planned to invest about US $75 million in the construction of a large textile factory near Dushanbe. However, the project was later abandoned due to financial problems.

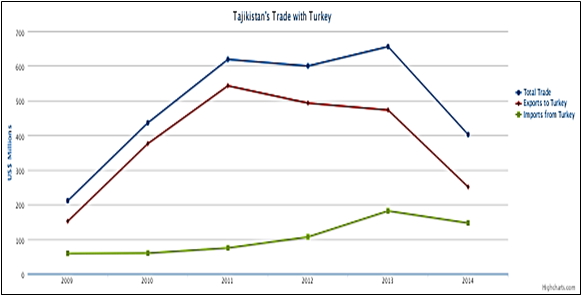

As data analysis for 2009-2013 shows, Turkey’s exports to Tajikistan and the importation of Tajik goods more than tripled with the trade turnover with Turkey amounting to $656.0 million or 12.4% in 2013 from the total combined volume of foreign trade. This suggests a steady increase in the proportion of Turkey’s foreign trade with Tajikistan, which in 2009 was only 5.9%.

From 2010-2013, Turkey remained the leading destination for Tajik exports. In 2013, Turkey imported Tajik goods amounting to $473.4 million, which was 40.7% of total exported goods, while maintaining a stable surplus. Imports reached $182.6 million or 4.4% of total imports into the country. The amount of exports exceeded import by 2.5 times and totaled $290,800,000.

For 2013, Tajikistan’s main exported goods to Turkey were cotton fiber, refined aluminum, leather, and hides. Tajikistan primarily imported Turkish goods and foodstuffs such as poultry, beef, and fruits as well as detergents, carpets and other textile floor coverings, plastic rubber products, ferrous metals, and heavy machinery.[5]

Figure 1. External trade turnover between Tajikistan and Turkey for 2009- 2014. (US$ millions)

Source: Statistical Yearbook “Tajikistan in figures 2015”, pgs. 343-370.

Source: Statistical Yearbook “Tajikistan in figures 2015”, pgs. 343-370.

However, in 2014 Tajik exports to Turkey declined by half, while Turkish exports to Tajikistan fell by 25%, which reduced Tajikistan’s trade surplus to $105 million (See Diagram 1).

Thus the total number of Tajik exports to Turkey was second to Switzerland (in 2013 – 1st) and 7th in imports. Among the CIS Member States to export to Turkey, Tajikistan occupies 7th place while placing 11th on importing goods from Turkey.[6]

It should be noted that the decline in trade between the two countries takes place against the background of a reduction in the total volume of Tajikistan’s foreign trade turnover. In particular, exports fell by 1.9% or $11.7 million, while imports fell 9.1% or $196.6 million. Experts in the country attributed this trend to the decrease in imports of wood and wood related products, vehicles, minerals, and finished food products as well as a decrease in the export volume of cotton, precious and semi-precious stones and metals, live animals, products of animal and vegetable origin.[7]

Soft Power

Among the priorities of Turkey’s soft power in Central Asia and Tajikistan in particular, we can highlight joint projects in the education and cultural spheres. Since 1991, the Turkish state, private entrepreneurs, and non-governmental organizations have opened many educational institutions in the region as part of the “Big Student Project”.[8]

Six joint Tajik-Turkish lyceums and boarding schools operated in Tajikistan until recently, the first of which opened in the city of Tursunzade in 1992 by an agreement between Tajikistan’s Ministry of Education and the Turkish educational institution “Shalola”. Later, it was decided at the ministry level to establish Tajik-Turkish lyceums in Dushanbe, Kulyab, Kurgan-Tube, Khujand and Khorog. Lyceums were opened in all of these cities with the exception of Khorog.[9]

Despite the fact that in 2013 “Shalola” paid taxes to the state budget amounting to more than five million somoni, and the unprecedented success of the students, which for over 10 years in international competitions won 484 medals, including 88 gold, 130 silver, and 266 bronze, Shalola’s status was revoked in 2015, and the lyceums have been converted into schools for gifted children.[10] The lyceums were closed at the request of the Turkey’s President Erdogan as “Shalola” is an affiliate organization of the Gülen movement “Khizmat”.[11] In addition, active Turkish language classes are being held at the TOMER center in the Turkish Embassy in Dushanbe.

Except for Turkmenistan, Tajik-Turkish cooperation in the field of education falls below that of other Central Asian states. For example, in neighboring Kyrgyzstan there are around 25 Turkish schools, including high schools and two universities, and 32 schools, lyceums, and the K.A. Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University in Kazakhstan. There is one high school and university in Turkmenistan while in Uzbekistan, prior to the cooling of relations, there were 65 Turkish educational institutions.[12]

It seems there is not exactly a significant impasse despite the linguistic heterogeneity between countries, which to a certain extent reduced the demand for Turkish high schools in the country.

Conclusion

For Turkey, cooperation with Tajikistan, in spite of some success in the trade and economic spheres, does not stand out in a special way and is simply a part of their foreign policy strategy in the region.

At this stage, the positions of Tajikistan and Turkey on international and regional issues are not an issue. At the same time, Turkey is the main haven for Tajik opposition members and organization such as Group-24, Youth for the revival of Tajikistan, and the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan as well. All these groups were deemed extremist in Tajikistan, and their members are wanted internationally. However, Dushanbe, unlike in Tashkent, does not react so sorely to the granting of asylum to their opponents. Economic expediency in normal relations has removed the issue of extraditing members of these groups from the agenda.

Tajikistan has also shown political acquiescence, especially concerning the closing of the Tajik-Turkish lyceums immediately after Erdogan’s request. This is in contrast to officials in Bishkek and Astana who, in spite of closer political relations with Turkey, have not taken such a definitive decision thus leaving the question of Turkish schools open ended.

Dushanbe is extremely interested in the development and deepening of trade and economic relations with Turkey and tries to avoid politicizing the relationship. At the same time, the political regime in Dushanbe is aimed at the complete secularization of society, with a certain apprehension seen in the growth of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, which was originally created by representatives of the Islamic Virtue Party. Improving the image of political Islam in Tajikistan can simultaneously improve the image of the banned Islamic Renaissance Party, which is an unacceptable condition for the regime. This factor can prove to be irritable and a further determining aspect in the two countries’ relations.

Ankara, in turn, especially after the restarting of relations with Moscow, will identify its interests, including in Tajikistan, and attempt to develop mutually beneficial trade and economic relations with the Central Asian country.

It seems that bilateral relations between Tajikistan and Turkey, despite some informal and ideological differences, have great, untapped potential. An attractive aspect for Tajikistan these days remains Turkey’s experience in the development of tourism, the textile industry, and processing of raw materials. In addition, in Tajik society there is a desire for modernization, economic development, and to build a stable society, which the Turkish model of development, taking into account its Eastern Muslim component, will be objectively considered as the most attractive.

References

[1] Troitsky, Yevgeny. “Turkey’s Policy in Central Asia.” Tomsk State University Journal 328, no. 51 (May 25, 2009): 84–88. http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/politika-turtsii-v-tsentralnoy-azii-1992-2000-gg.

[2] Ismail Cem, “Turkey: Setting Sail to the 21st Century,” Perceptions Volume II, no. 3 (November 1997), http://sam.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/IsmailCem1.pdf.

[3] Winrow, Gareth M. Turkey in Post-Soviet Central Asia. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1995.

[4] Alieva, Rafoat. “On the Issue of Integration of the Tajik Republic in the World Community.” Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Serija 4. Istorija. Regionovedenie. Mezhdunarodnye otnoshenija, no. 2 (February 2010): 119–24. doi:10.15688/jvolsu4.2010.2.16.

[5] Shkvaria, L. V., V. I. Rusakovich, and D. B. Lebedeva. “External Economic Relations of the Republic of Tajikistan with the Countries of Asia: Current Trends.” Журнал включен в Перечень ВАК, no. 78 (June 2015). http://uecs.ru/uecs-78-782015/item/3551-2015-06-08-06-21-22.

[6] Turkey’s Trade and Economic Relations with CIS States. Moscow: CIS Executive Committee, 2015. www.e-cis.info/foto/pages/25185.docx.

[7] “Foreign Trade of Tajikistan Decreases by Almost $1.3 Billion over Past 2 Years.” September 15, 2001. Accessed October 5, 2016. http://akipress.com/news:582317/.

[8] Haas, Karim. “Особенности внешней политики Турции в Центральной Азии” [Features of Turkish Foreign Policy in Central Asia]. Army & Society 35, no. 3 (2013): 1–7. http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/osobennosti-vneshney-politiki-turtsii-v-tsentralnoy-azii.

[9] Brletich, Samantha. “Tajikistan, Turkey and the Gülen Movement.” August 21, 2015. Accessed October 5, 2016. http://thediplomat.com/2015/08/tajikistan-turkey-and-the-gulen-movement/.

[10] Dirikom, Mehmet Munis. “Политика на пути к миру и стабильности”: интервью посла Турции в Таджикистане [“Politics on the road to peace and stability”: An interview with Turkey’s ambassador to Tajikistan]. (October 27, 2011). http://avesta.tj/2011/10/27/politika-na-puti-k-miru-i-stabilnosti-intervyu-posla-turtsii-v-tadzhikistane/.

[11] Regnum. В Таджикистане не стали продлевать лицензию турецким лицеям [No renewed licenses for Turkish lyceums in Tajikistan]. January 02, 2015. https://regnum.ru/news/cultura/1882283.html.

[12] Politforum. “Движение Фетхуллы Гюлена” [Gülen Movement]. 2013. n.d. http://politforumi.com/panel/uploads/Ambasadori-Religia/Dvizenie-Fethullt-Gelena.pdf.

Author: Khursand Khurramov, political scientist (Tajikistan, Dushanbe)

The opinion of the author may not necessarily reflect that of cabar.asia

“Worthy of note is that, despite a modest contribution of Iran to Tajikistan’s economy, it is thanks to its close cooperation that Dushanbe will be able to achieve three strategic goals: break a communication deadlock, ensure energy and food security”, – says Khursand Khurramov, a political analyst, specially for cabar.asia, giving his forecasts on the development of the Tajik-Iranian relations.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“Tajikistan is waiting for Russia to create certain programs within the framework of the EaEU for the real sector of the economy, joint industrialization along the lines of the activities of the Russian-Kyrgyz Development Fund, and the realization of Dushanbe’s energy projects as well as the solving of disputes with Uzbekistan. Additionally, the agenda calls for the creation of direct rail links with other EaEU member-states and compensation for what Tajik officials view to be unavoidable short-term losses in customs duties for Tajikistan,” – political scientist Komron Khidoyatzoda examines the difficult questions and expectations of Tajikistan regarding cooperation with the EaEU in this cabar.asia exclusive.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“It must be admitted that today, outside of the bureaucrats’ bravura proclamations of hundreds of thousands of newly created jobs in Tajikistan and the sparkling official unemployment statistics, there have been no real successes in controlling the demographic situation in the country,” – Mikhail Petrushkov, a specialist from Dushanbe, analyses the demographic situation in Tajikistan in this cabar.asia exclusive.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“According to the basic parameters of food security, Tajikistan is currently approaching the thresholds, being behind all other Central Asian states. In terms of affordability of staple foods for the population, the import ratio to domestic production, household spending on food, the situation in the country looks worse than in the countries of the “Arab Spring” on the eve of the social and political unrest of 2010 – 2012″, – writes in his article, specially for cabar.asia, a political analyst from Tajikistan, Parviz Mullojanov.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

“If Dushanbe is able to come to another agreement with Iran, then this is the country, in our view, that would be able to invest in the Rogun HPP. Additionally, Iran will not consider Uzbekistan’s complaints, especially since Tajikistan already has the legitimate reasons and the World Bank’s favorable findings on Rogun’s construction,” – Tajik experts Hamidjon Arifov and Nurali Davlatov examine the perspectives and problems facing the resolution of hydroelectric issues in this cabar.asia exclusive.

Follow us on LinkedIn!